If you’re a serious Phantasy Star or Lunar fan, you’ll be like a kid in a Naula cake shop at Rebecca Capowski’s website.

Thanks to Rebecca, English speakers now can immerse themselves further into these worlds they love through novels, director interviews, dev-team discussion, and even more accurate translations of the games themselves.

Moreover, it’s clear Rebecca is truly passionate about these games, their characters, and their stories. You won’t find one ad on her site, nor squeals of “like and subscribe!” assaulting your senses. Translation is grueling, slow work, and the amount of content she’s translated simply for hobby is mind-blowing.

She also officially worked on the English translation of Phantasy Star Online 2, credited as a Language Specialist!

Rebecca is a talented writer, as well, so it seems appropriate that we deliver Episode 4 of Found in Fanslation to you through text!

Whether you’re into in-game lore enough to want to finally learn what “AW” means, or you simply want to better get to know your favorite characters, check out her website: ScenaryRecalled.com

Found in Fanslation: Ep 04 – Text Adventures with Rebecca Capowski

Part 1: Phantasy Star and LUNAR (this page)

Part 2: Translation/Localization and Learning Japanese (next page)

PHANTASY STAR

What makes Phantasy Star so special to you?

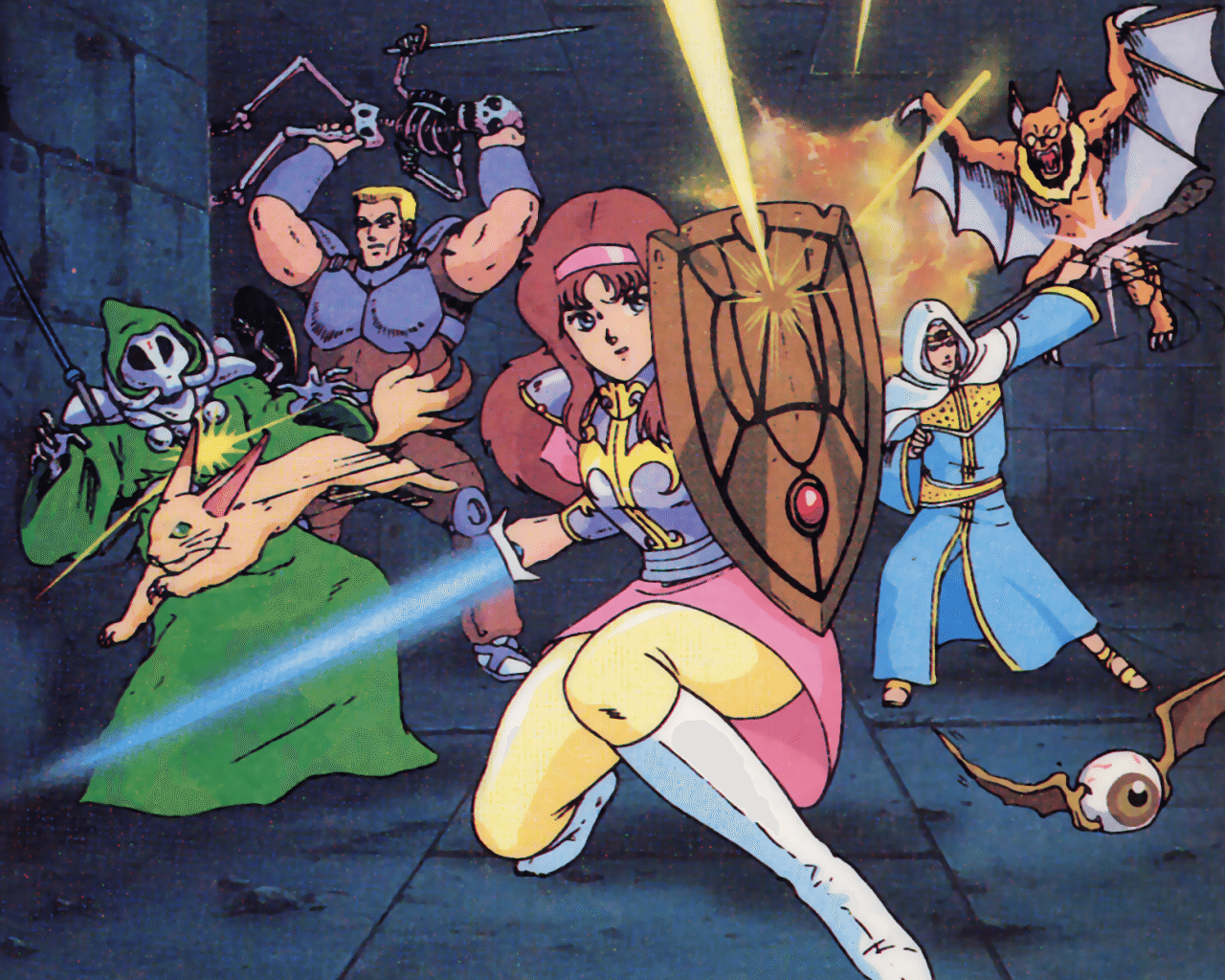

A great part of it was the impact Phantasy Star II had on me as a child. I first encountered it in a feature in Game Player’s magazine, and it was like nothing I’d played. The characters had more or less regular jobs instead of knight & wizard classes, which were described in language that was naturalistic but rather cynical and novel-like instead of perfunctory. The settings looked so sharp and bright, nothing like the stone castles that populated RPGs up to that point.

That impression only deepened when I got the game for Christmas: [In PSII,] quests didn’t end happily. The larger nature of the conflict, and what you had to do to make things better, was unclear. Much of the story was told through the environment and mood, with discoveries that were at odds with the look of the game — the world was on the surface very bright but very wrong underneath.

Nothing was underlined; the player was allowed to draw conclusions for herself. The ending, with its idea that a story could end unhappily, with the protagonists sacrificing themselves nobly instead of living happily ever after, and that the main “boss” was not an extrinsic evil overlord but weaknesses in the people themselves, blew my young mind. It’s really taken for granted how much of a departure that game was from anything on consoles at the time.

Outside of that, I think there are a lot of things that set the classic series apart. There’s that bright and sharp presentation, from the graphics & scrolling dungeons of I to the world of II to the manga panels of IV. There’s a larger role for women than typical: the hero in the first; the [antagonists] in the second; the mentor in the fourth. (Even III has a preponderance of female party members, even if it’s just to provide marriage prospects.)

The sci-fi elements & setting were unusual at the time for RPGs, of course, but Phantasy Star remains distinctive, I think, in how it marries that to a vivid color palette. Most sci-fi RPGs (Shadowrun, Mass Effect) fall into a dank cyberpunk look, or sleek, military blues and grays, or a clean, Apple-like look with a lot of white and glass. Phantasy Star has this attitude of fun and brightness in its visual component that nevertheless sits comfortably next to a sleek, high-tech approach to its worldbuilding and stories.

Which is your favorite Phantasy Star, and why?

II hands down, for the reasons listed above. Gameplay-wise, it’s a style of RPG that’s not much used these days, where the primary obstacles are the levels themselves – instead of building up to a series of boss encounters, gameplay progression revolves more around managing resources and negotiating the environment to survive the given dungeon. That’s an obstacle for a lot of folks, but the total package has given me more than most any other game.

Who’s your favorite Phantasy Star character, and why?

I like a lot of Phantasy Star characters: Alis, who’s determined to venture forth and set things right, clad in flouncy pink and all; Kyra, with her reverence for heroism and her can-do attitude; Lutz, for what he represents in PSII, a bastion of purpose in a world devoid of it.

The main draws for PS for me, though, are the settings and atmosphere. It’s the rare RPG series that (save for IV, arguably) is actually not character-focused. The games are overall more about negotiating the worlds, discovering their nature, and the state of society and the technology that drives it. (This is in part why III doesn’t work well: romance is inherently character-driven, yet the game sticks with the traditional PS method of more world-driven storytelling.)

One thing I like about Phantasy Star characters is that, save for III (and despite the lineages of Alis and Rolf), they don’t function as the typical RPG “holy chosen one” archetypes. They’re just proactive people who identify a problem and take it upon themselves to set out and solve it. They’re doing a job, more often than not.

Phantasy Star III is not well regarded by most PS fans, but you’ve done extraordinary work on translating materials for its universe. What motivated you to do so?

Thank you for the kind words. To be blunt: I think it deserves to suck on its own terms.

I went into the script wondering if anything was left out of the U.S. version of the story — and indeed there was. For instance, there’s a very definite sense in the Japanese script that by choosing one side during the marriage events, you are causing great pain or damage to the other. More detail is given on the sad fate of Cille and Shusoran if you marry Lena, and Lyle is given a heroic but tragic death. If rejected, younger Laia/Laya leaves Lein/Nial her pendant so he can return to her — in case he changes his mind, it’s implied — and the next thing she sees is it around the neck of his son by another woman.

There’s a greater sense of loss in the Japanese version and attention to the endings of the characters who leave the direct focus of the story through your own actions. And there are touching small moments, such as man who won’t leave the graves of his family in Cille, or Queen Sari reflecting that Ayn met his end as befitting a king, or the man who witnesses Lyle’s last moments alone without realizing their significance. In place of this material, the U.S. version substitutes largely empty banter – which is odd, since the official PSII translation didn’t shy away from its source’s depth.

![]()

I don’t think PSIII was successful overall (and I don’t agree with the recent movement to canonize it as an overlooked gem or even the best classic PS game; some people get so carried away by a desire to be iconoclastic that they overlook, you know, actual quality), but I have more of an appreciation for what it was trying to do now.

LUNAR

What makes the world of Lunar so special to you?

I was introduced to Lunar by a pen pal I met through a gaming magazine. He had videotaped practically every anime cutscene in both games, and he sent me a copy of the tape, complete with a very detailed and enthusiastic handwritten synopsis of the games’ stories for context. I loved it. I got a Sega CD and played the games for myself shortly afterward.

As opposed to Phantasy Star, my attachment to Lunar is very character-focused. I actually have a lot of frustration with the Lunar worldview — it seems very selfish and simplistic at times, at least as depicted in the main games.

I think Ghaleon is a real achievement of character, particularly for the time; I really like Strolling School’s simple tale of a school-age friendship; and I love the entire cast Akari Funato introduced in the manga, as well as her excellent characterization of Dyne.

The casts in general have a lot of charm, and like Phantasy Star, the games feature terrific, bold use of color. The creators also really knew how to use the new capabilities of the CD format – Lunar wouldn’t have gotten where it did without the anime cutscenes or symphonic music or John Truitt’s voice work or “COOOOOOME BAAAAACK TOOOOO MEEEEEEEEEEE”.

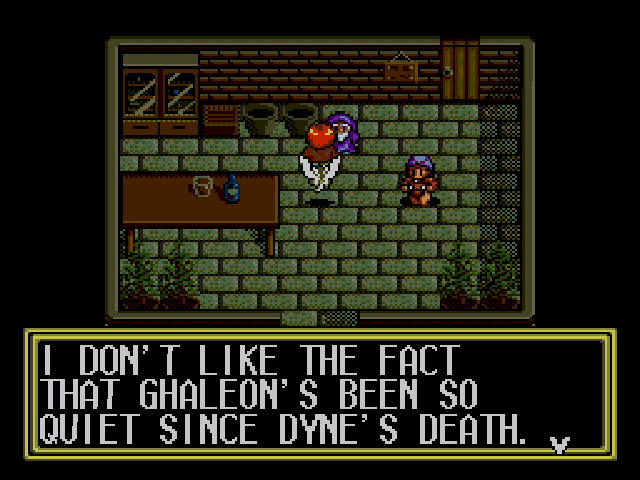

What is the “Ghaleon didn’t know what was going on” theory in Lunar TSS (Sega CD) mentioned on your page?

In the Sega CD version, the inciting incident for Ghaleon’s turn is Dyne losing his power taking care of a crisis that would have been Althena’s responsibility to resolve, had she not been off gallivanting as a human. Ghaleon perceives Althena as abusing Dyne’s service and being too willing to sacrifice the humans under her, concluding that she is therefore an unjust god who needs to be deposed. Dyne’s pretending to be dead at the start of the game, and his survival is a surprise to the player — but not Ghaleon, who was there for Dyne’s depowering.

He doesn’t disabuse Alex of the notion that Dyne’s dead, because why would he, but the game takes pains to underline that he knows the truth: He’s not the least bit surprised at Dyne’s survival in the confrontation they have midgame at Myght’s Tower; after the truth about Dyne comes out, there’s a pair of NPCs in Marke, I believe, who expressly serve to explain the situation to any confused players (something like ” If Ghaleon knew Master Dyne survived, why was he so angry?” “Ghaleon knew Dyne was alive all along! He must’ve lost it when his idol was so humiliated…”).

Ghaleon’s dialogue pre-reveal is careful to play up his anger and indignance at Dyne being “tossed aside” and being treated as disposable by Althena, setting up the player to accept later a motivation for Ghaleon’s actions that doesn’t necessarily include Dyne’s death (just his depowering and perceived unjust treatment).

Despite this, there were a few people in the early internet fandom (pre-SSS) who still got confused and thought that, well, since Ghaleon says Dyne is dead at the start, the stuff later on couldn’t be right, and that must mean he never knew Dyne was alive, and the motivation for the entire story is just one big “oops”.

(It’s like if someone claimed: no, hey, Cloud was in SOLDIER, he *says* he was in SOLDIER earlier in the game, so the parts later on can’t be right!)

There were never many, but they included one influential fan who featured the idea in their fan works and pushed for its inclusion in fan resources and whatnot. The idea otherwise would’ve gone the way of General Leo resurrection rumors, but since SSS replaced TSS in the public eye shortly after, there were fewer and fewer people who had actually played the original TSS around to fact-check in the face of this person’s persistence, and it led to this weird fanfic replacing the actual TSS story in most Lunar resources online.

I find this extremely frustrating; it’s the responsibility of fan communities to showcase what’s special about our favorite works to the world at large, and this whole debacle seems like a dereliction of duty, not to put it too grandiosely. It’s taking a story that was advanced for its day, one of the first game stories to have a villain motivated by something other than a lust for power and something that made TSS unique and historically significant, and substituting an extremely stupid one due to personal politics – and it’s so dumb, from the idea itself to how it’s defended. I’ve seen the weirdest, most tortured explanations for it, up to and including declaring certain portions of the games to be non-canon and inventing entire cutscenes that don’t exist.

What’s the most interesting thing you learned about the world of Lunar while translating the mangas?

![]()

I think one of the biggest contributions of the Vane Airship manga is how it casts the dynamic between Ghaleon and Dyne as essentially a father-son relationship, which makes so much sense both in context of the characters themselves and Lunar’s larger themes. Since Dyne was the Dragonmaster and made a decision that Ghaleon didn’t understand or accept, that lends itself to the interpretation that Ghaleon looked up to Dyne, not vice versa.

It doesn’t make sense to put Ghaleon on the younger, more immature side of the equation, though, as he functions in Silver Star — which is a story about children taking over the world from their parents — as essentially a parent who won’t let his kids grow up. Casting Ghaleon as the parent and Dyne as the child is more organic to their personalities and allows their interactions to echo and foreshadow their disagreement in Silver Star, as well as the main themes of the game.

It’s the exact opposite of what one might initially expect, but it ends up making complete sense, and it’s an excellent example of how supplemental works can bolster the original work by addressing themes from a different angle or fleshing out characters who are crucial to a plot but, due to practical considerations, can’t have the spotlight in-game. The more I go over Tales of the Vane Airship, the more I’m amazed by just how much Akari Funato knocked it out of the park on that book in both art and story.

Continue to Part 2: Translation vs. Localization and Learning Japanese